UVM News and Readings: April 2025

The Liturgical Year

Very Rev. Dom Prosper Guéranger Abbot of Solesmes, 1833-1875

The History, Mystery, and Practice of Passiontide and Holy Week

The History of Passiontide and Holy Week

After having proposed the forty-days’ Fast of Jesus in the Desert to the meditation of the Faithful, during the first four weeks of Lent, the Holy Church gives the two weeks, which still remain before Easter, to the commemoration of the Passion. She would not have her children come to the great Day of the immolation of the Lamb, without their having prepared for it by compassionating with him in the Sufferings he endured in their stead.

The most ancient Sacramentaries and Antiphonaries of the several Churches attest, by the Prayers, the Lessons, and the whole Liturgy of these two weeks, that the Passion of our Lord is now the one sole thought of the Christian world. During Passion Week, a Saint’s Feast, if it occur, will be kept; but Passion Sunday admits no Feast, however solemn it may be; and even on those which are kept during the days intervening between Passion and Palm Sundays, there is always made a commemoration of the Passion, and the holy Images are not allowed to be uncovered.

We cannot give any historical details upon the first of these two Weeks; its ceremonies and rites have always been the same as those of the four preceding ones. We, therefore, refer the reader to the following Chapter, in which we treat of the mysteries peculiar to Passiontide. The second week, on the contrary, furnishes us with abundant historical details; for there is no portion of the Liturgical Year, which has interested the Christian world so much as this, or which has given rise to such fervent manifestations of piety.

This week was held in great veneration even as early as the 3rd century, as we learn from St. Denis, Bishop of Alexandria, who lived at that time. (Epist. ad Basilidem, Canon i) In the following century, we find St. John Chrysostom calling it the Great Week: (Hom. xxx in Genes.) “not,” says the holy Doctor, “that it has more days in it than other weeks, or that its days are made up of more hours than other days; but we call it Great, because of the great Mysteries which are then celebrated.” We find it called also by other names: the Painful Week (Hebdomada Pœnosa), on account of the Sufferings of our Lord Jesus Christ, and of the fatigue required from us in celebrating them; the Week of Indulgence, because sinners are then received to penance; and, lastly, Holy Week, in allusion to the holiness of the Mysteries which are commemorated during these seven days. This last name is the one, under which it most generally goes with us; and the very days themselves are, in many countries, called by the same name, Holy Monday, Holy Tuesday, Good Friday, Holy Saturday.

The severity of the Lenten Fast is increased during these its last days; the whole energy of the spirit of penance is now brought out. Even with us, the dispensation which allows the use of eggs ceases towards the middle of this Week. The Eastern Churches have kept up far more of the ancient traditions; and their observance of abstinence, during these days, is far more severe than ours. The Greeks call this week Xérophagia, that is, the week when no other food is allowed but that which is dry, such as bread, water, salt, dried fruits, raw vegetables: every kind of seasoning is forbidden. In the early ages, Fasting, during Holy Week, was carried to the utmost limits that human nature could endure. We learn from St. Epiphanius, (Exposito fidei, ix Hæres. xxii) that there were some of the Christians who observed a strict fast from Monday morning to cock-crow of Easter Sunday. Of course, it must have been very few of the Faithful who could go so far as this. Many passed two, three, and even four consecutive days, without tasting any food; but the general practice was to fast from Maundy Thursday evening to Easter morning.

Another of the ancient practices of Holy Week were the long hours spent, during the night, in the Churches. On Maundy Thursday, after having celebrated the divine mysteries in remembrance of the Last Supper, the faithful continued a long time in prayer. (St. John Chyrsostom, Hom. xxx in Genes.) The night between Friday and Saturday was spent in one uninterrupted vigil, in honor of our Lord’s Burial. (St Cyril of Jerusalem, Catech. xviii.) But the longest of all these vigils was that of Saturday, which was kept up till Easter Sunday morning: it was one in which the whole of the people joined: they assisted at the final preparation of the Catechumens, as also at the administration of Baptism, nor did they leave the Church until after the celebration of the Holy Sacrifice, which was not over till sunrise.

Cessation from servile work was, for a long time, an obligation during Holy Week. The civil law united with that of the Church in order to bring about this solemn rest from toil and business, which so eloquently expresses the state of mourning of the Christian world. The thought of the sufferings and death of Jesus was the one pervading thought: the divine Offices and Prayer were the sole occupation of the people: and, indeed, all the strength of the body was needed for the support of the austerities of fasting and abstinence. We can readily understand what an impression was made upon men’s minds, during the whole of the rest of the year, by this universal suspension of the ordinary routine of life. Moreover, when we call to mind how, for five full weeks, the severity of Lent had waged war on the sensual appetites, we can imagine the simple and honest joy, wherewith was welcomed the feast of Easter, which brought both the regeneration of the soul, and respite to the body.

The Mystery of Passiontide and Holy Week

The holy Liturgy is rich in mystery, during these days of the Church’s celebrating the anniversaries of so many wonderful events; but as the principal part of these mysteries is embodied in the rites and ceremonies of the respective days, we shall give our explanations according as the occasion presents itself. Our object, in the present Chapter, is to say a few words respecting the general character of the Mysteries of these two Weeks.

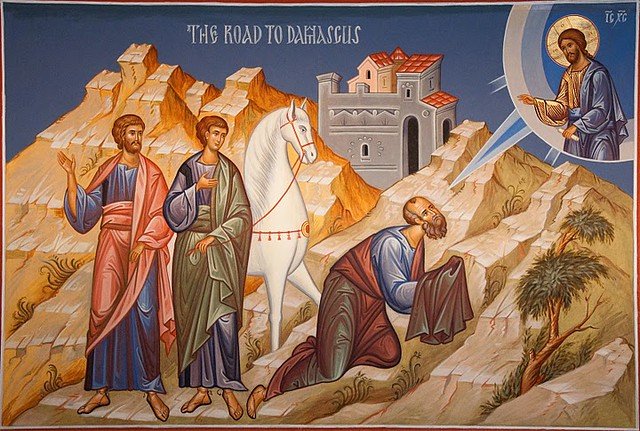

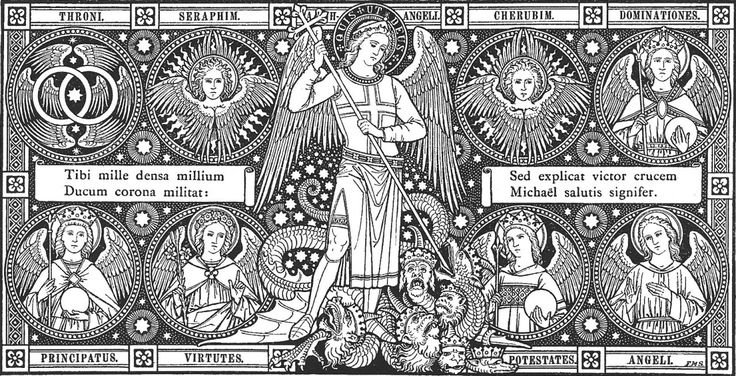

We have nothing to add to the explanation, already given in our “Lent,” on the mystery of Forty. The holy season of expiation continues its course, until the fast of sinful man has imitated, in its duration, that observed by the Man-God in the desert. The army of Christ’s faithful children is still fighting against the invisible enemies of man’s salvation; they are still vested in their spiritual armor, and, aided by the Angels of light, they are struggling hand to hand with the spirits of darkness, by compunction of heart and by mortification of the flesh.

As we have already observed, there are three objects which principally engage the thoughts of the Church during Lent. The Passion of our Redeemer, which we have felt to be coming nearer to us each week; the preparation of the Catechumens for Baptism, which is to be administered to them on the Easter eve; the Reconciliation of the public Penitents, who are to be re-admitted into the Church, on the Thursday, the day of the Last Supper. Each of these three objects engages more and more the attention of the Church, the nearer she approaches the time of their celebration.

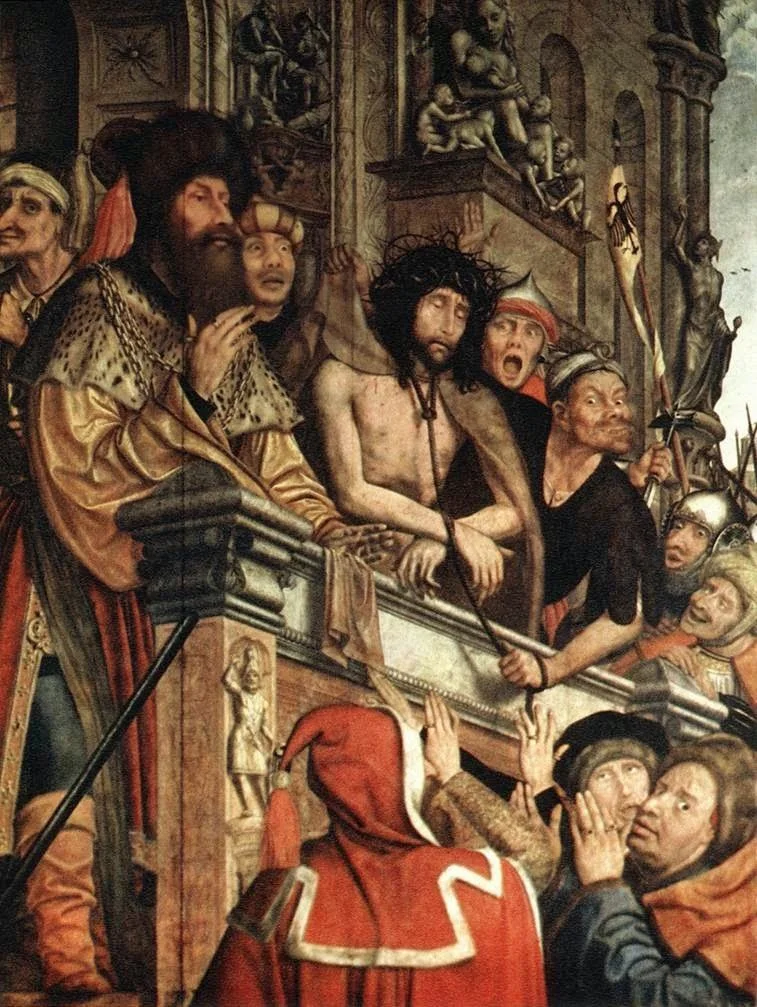

The miracle performed by our Savior, almost at the very gates of Jerusalem, and by which he restored Lazarus to life, has roused the fury of his enemies to the highest pitch of frenzy. The people’s enthusiasm has been excited at seeing him, who had been four days in the grave, walking in the streets of their City. They ask each other, if the Messias, when he comes, can work greater wonders than these done by Jesus, and whether they ought not at once to receive this Jesus as the Messias, and sing their Hosanna to him, for he is the Son of David? They cannot contain their feelings:—Jesus enters Jerusalem, and they welcome him as their King. The High Priests and Princes of the people are alarmed at this demonstration of feeling; they have no time to lose; they are resolved to destroy Jesus. We are going to assist at their impious conspiracy: the Blood of the Just Man is to be sold, and the price put on it is thirty silver pieces. The Divine Victim, betrayed by one of his Disciples, is to be judged, condemned, and crucified. Every circumstance of this awful tragedy is to be put before us by the Liturgy, not merely in words, but with all the expressiveness of a sublime ceremonial.

The Practice of Passiontide and Holy Week

The past four weeks seem to have been but a preparation for the intense grief of the Church during these two. She knows that men are in search of her Jesus, and that they are bent on his Death. Before twelve days are over, she will see them lay their sacrilegious hands upon him. She will have to follow him up the hill of Calvary; she will have to receive his last breath; she must witness the stone placed against the Sepulcher where his lifeless body is laid. We cannot, therefore, be surprised at her inviting all her children to contemplate, during these weeks, Him who is the object of all her love and all her sadness.

But our Mother asks something more of us than compassion and tears; she would have us profit by the lessons we are taught by the Passion and Death of our Redeemer. He himself, when going up to Calvary, said to the holy women, who had the courage to show their compassion even before his executioners: “Weep not over me; but weep for yourselves and for your children.” (Luke 23:28) It was not that he refused the tribute of their tears, for he was pleased with this proof of their affection; but it was his love for them that made him speak thus. He desired, above all, to see them appreciate the importance of what they were witnessing, and learn from it how inexorable is God’s justice against sin.

During the four weeks that have preceded, the Church has been leading the Sinner to his conversion; so far, however, this conversion has been but begun; now, she would perfect it. It is no longer our Jesus fasting and praying in the Desert, that she offers to our consideration; it is this same Jesus, as the great Victim immolated for the world’s salvation. The fatal hour is at hand; the power of darkness is preparing to make use of the time that is still left; the greatest of crimes is about to be perpetrated. A few days hence, and the Son of God is to be in the hands of sinners, and they will put him to death. The Church no longer needs to urge her children to repentance; they know too well, now, what sin must be, when it could require such expiation as this. She is all absorbed in the thought of the terrible event, which is to close the life of the God-Man on earth; and by expressing her thoughts through the holy Liturgy, she teaches us what our own sentiments should be.

The pervading character of the prayers and rites of these two weeks, is a profound grief at seeing the Just One persecuted by his enemies even to death, and an energetic indignation against the deicides. The formulas, expressive of these two feelings, are, for the most part, taken from David and the Prophets. Here, it is our Savior himself, disclosing to us the anguish of his soul; there, it is the Church, pronouncing the most terrible anathemas upon the executioners of Jesus. The chastisements, that is to befall the Jewish nation, is prophesied in all its frightful details; and on the last three days, we shall hear the Prophet Jeremias uttering his Lamentations over the faithless City. The Church does not aim at exciting idle sentiment; what she principally seeks, is to impress the hearts of her children with a salutary fear. If Jerusalem’s crime strike them with horror, and if they feel that they have partaken of her sin, their tears will flow in abundance.

Let us, therefore, do our utmost to receive these strong impression, too little known, alas! by the superficial piety of these times. Let us reflect upon the love and affection of the Son of God, who has treated his creatures with such unlimited confidence, lived their own life, spent his three and thirty years amidst them, not only humbly and peaceably, but in going about, doing good. (Acts 10:38) And now, this life of kindness, condescension and humility, is to be cut short by the disgraceful dath, which none but slaves endured—the death of the Cross. . . . . Let us hope that, by God’s mercy, the holy time we are now entering upon will work such a happy change in us, that, on the Day of Judgment, we may confidently fix our eyes on Him we are now about to contemplate crucified by the hands of sinners. The Death of Jesus puts the whole of nature in commotion; the midday sun is darkened, the earth is shaken to its very foundations, the rocks are split;—may it be, that our hearts, too, be moved, and pass from indifference to fear, from fear to hope, and, at length, from hope to love; so that, having gone down, with our Crucified, to the very depths of sorrow, we may deserve to rise again with him unto light and joy, beaming with the brightness of his Resurrection upon us, and having within ourselves the pledge of a new life, which shall then die no more!